Drone Prices

Click Here for Tutorials!

Here you can look at articles, videos, and more!

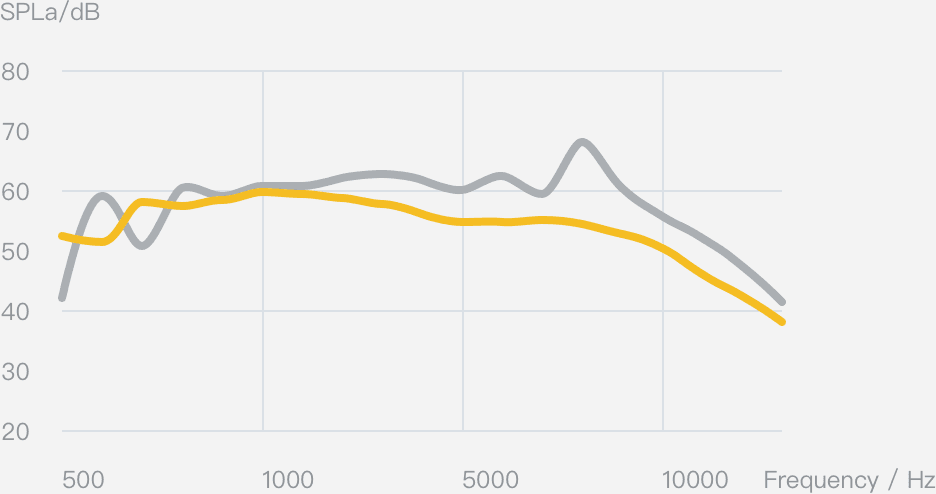

On November 1st, 2017, The Verge anounced that the Dji Mavic Pro Platinum is unbeleivebly quiet. They said, "One of the things you come to anticipate after flying a drone for a while is how the people around you will react. If you take off or land near someone who’s unfamiliar with the technology, a few people will be curious; many others will get upset. A loud machine making an angry buzzing sound a few feet from your head is something many humans have an instinctively negative reaction to. A phrase like "angry buzzing” sounds subjective, but it’s not just my opinion. A NASA study found that the sounds of drones were roughly twice as annoying to the average person as the same volume of noise produced by a car or truck. The noise of a drone is more annoying at the same volume because it’s a much higher frequency, one that happens to be particularly unpleasant to the ears of most humans. DJI, the world’s most popular brand of consumer drones, is trying to do something about that. Its Mavic Pro Platinum, released back in August of this year, comes with a set of redesigned rotor blades that the company claims make the unit 60 percent quieter than the previous model. It tweaked the design of the blades by adding what’s known as a “raked wingtip.” The blades curve through the middle and angle back and up at the tip. To optimize for the new design, DJI also added electronic speed controllers that spin them at a different rate. I stopped by DJI’s office last week to hear the difference for myself, and to my ears at least, the results were impressive. When you launch indoors and hover the drone a few feet from you, the sound is more like a loud desk fan. You wouldn’t miss it, but it no longer sounds like an angry, oversized bee. Some YouTube reviewers have pointed out that, in terms of decibels, there is no real change between the old rotors and the new. That’s true, but it misses the point. It’s not a significant difference in volume, but rather in pitch. Once you get the drone in the air, the difference is even more striking. At a height of about 30 feet, you can still hear the whine of the original Mavic Pro loud and clear. At that same distance, the sound of the reengineered Mavic Pro Platinum almost completely fades away. If you’re actively listening for it, it’s still detectable, but the average bystander walking below wouldn’t pick up on the fact that something is close overhead. You can see a little visualization of the difference below. The gray spike around 8,000Hz is what really bothers most human ears with the old Mavic drone. The yellow line is a comparison of the sound produced by the new one. As someone who flies drones often, this is a welcome improvement. I enjoy flying outdoors, but hate to ruin the experience for other nature lovers who may feel threatened or annoyed by the drone. Cutting back on the sound is a big piece of making the experience pleasant for everyone. I’m of two minds about what this means for public perception and governmental regulation of drones in the future, however. In the past, drone advocates have dismissed fears about how this technology could be used for spying or surveillance by pointing out, correctly, that it wasn’t very subtle. If you wanted to peep into a fifth-story window and not get caught, you would have a much easier time with a telephoto lens than a consumer drone. The quieter drones get, the harder it is to make the case that they aren’t powerful tools for invading other people’s privacy. On the other hand, quieter drones will be far easier to integrate into everyday life. The NASA study was commissioned as part of the agency’s larger effort to imagine what the next generation of aviation will look like, and how large numbers of autonomous airborne vehicles can be safely introduced into the skies above cities and towns. Making drones way less annoying is going to be key to the success or failure of initiatives like Amazon Prime Air. It was announced last week that the Department of Transportation is preparing to review applications from municipalities around the US that want to test advanced drone operations. The aim is to have at least five projects running over the next three years that will test out missions like autonomous delivery over populated areas, flights beyond the operator’s line of sight, and flights at night. This technology is moving from fantasy to reality at a steady pace. Last but not least, this demo made me wonder, what took so long? The design changes to the rotors aren’t being billed as some innovative breakthrough, just a common sense application of knowledge that has existed in the aerospace world for decades. DJI says they aren’t any more expensive to produce. (In fact you get better battery life with the new system than with older models.) But they do require careful design and testing. DJI can afford to pump some engineering resources into things like this, while most competitors can’t. Hearing the Mavic Platinum in action is a reminder that DJI is light-years ahead of the pack when it comes to innovation in the consumer drone space. From high-level computer vision techniques down to the little details of how to shape the plastic rotors that actually get your gadget off the ground, no one else comes close at the moment. One of the things you come to anticipate after flying a drone for a while is how the people around you will react. If you take off or land near someone who’s unfamiliar with the technology, a few people will be curious; many others will get upset. A loud machine making an angry buzzing sound a few feet from your head is something many humans have an instinctively negative reaction to. A phrase like “angry buzzing” sounds subjective, but it’s not just my opinion. A NASA study found that the sounds of drones were roughly twice as annoying to the average person as the same volume of noise produced by a car or truck. The noise of a drone is more annoying at the same volume because it’s a much higher frequency, one that happens to be particularly unpleasant to the ears of most humans. DJI, the world’s most popular brand of consumer drones, is trying to do something about that. Its Mavic Pro Platinum, released back in August of this year, comes with a set of redesigned rotor blades that the company claims make the unit 60 percent quieter than the previous model. It tweaked the design of the blades by adding what’s known as a “raked wingtip.” The blades curve through the middle and angle back and up at the tip. To optimize for the new design, DJI also added electronic speed controllers that spin them at a different rate. I stopped by DJI’s office last week to hear the difference for myself, and to my ears at least, the results were impressive. When you launch indoors and hover the drone a few feet from you, the sound is more like a loud desk fan. You wouldn’t miss it, but it no longer sounds like an angry, oversized bee. Some YouTube reviewers have pointed out that, in terms of decibels, there is no real change between the old rotors and the new. That’s true, but it misses the point. It’s not a significant difference in volume, but rather in pitch. Once you get the drone in the air, the difference is even more striking. At a height of about 30 feet, you can still hear the whine of the original Mavic Pro loud and clear. At that same distance, the sound of the reengineered Mavic Pro Platinum almost completely fades away. If you’re actively listening for it, it’s still detectable, but the average bystander walking below wouldn’t pick up on the fact that something is close overhead. You can see a little visualization of the difference below. The gray spike around 8,000Hz is what really bothers most human ears with the old Mavic drone. The yellow line is a comparison of the sound produced by the new one. As someone who flies drones often, this is a welcome improvement. I enjoy flying outdoors, but hate to ruin the experience for other nature lovers who may feel threatened or annoyed by the drone. Cutting back on the sound is a big piece of making the experience pleasant for everyone. I’m of two minds about what this means for public perception and governmental regulation of drones in the future, however. In the past, drone advocates have dismissed fears about how this technology could be used for spying or surveillance by pointing out, correctly, that it wasn’t very subtle. If you wanted to peep into a fifth-story window and not get caught, you would have a much easier time with a telephoto lens than a consumer drone. The quieter drones get, the harder it is to make the case that they aren’t powerful tools for invading other people’s privacy. On the other hand, quieter drones will be far easier to integrate into everyday life. The NASA study was commissioned as part of the agency’s larger effort to imagine what the next generation of aviation will look like, and how large numbers of autonomous airborne vehicles can be safely introduced into the skies above cities and towns. Making drones way less annoying is going to be key to the success or failure of initiatives like Amazon Prime Air. It was announced last week that the Department of Transportation is preparing to review applications from municipalities around the US that want to test advanced drone operations. The aim is to have at least five projects running over the next three years that will test out missions like autonomous delivery over populated areas, flights beyond the operator’s line of sight, and flights at night. This technology is moving from fantasy to reality at a steady pace. Last but not least, this demo made me wonder, what took so long? The design changes to the rotors aren’t being billed as some innovative breakthrough, just a common sense application of knowledge that has existed in the aerospace world for decades. DJI says they aren’t any more expensive to produce. (In fact you get better battery life with the new system than with older models.) But they do require careful design and testing. DJI can afford to pump some engineering resources into things like this, while most competitors can’t. Hearing the Mavic Platinum in action is a reminder that DJI is light-years ahead of the pack when it comes to innovation in the consumer drone space. From high-level computer vision techniques down to the little details of how to shape the plastic rotors that actually get your gadget off the ground, no one else comes close at the moment."

On November 2016, Airspace release's an article stateing "With 40 million fans, $100,000 purses, and crashes galore, drones take the track." They said, "Zachry Thayer expected that the competition for this drone race would be intense, so he just tries to be in the moment, to focus on the routine: video and power checks, safety clearance, and then the countdown—and they’re off! Six 800-gram quadcopters spring into the course. Thayer and his competition are wearing goggles that receive a video feed from cameras mounted on their drones, giving them a first-person view, or FPV. The drones zip over my head in the spectator stands sounding like Formula One cars made hysterical by helium. But I barely notice. I’m “in” one of the drones using my own pair of FPV goggles, streaking at nearly 80 mph over the nets that protect the spectators, through the first check gate—a neon circle—then banking a 90-degree left over a reflecting pool, and down the straightaway that runs the 300-foot length of the building. Then the drone shoots up, loops around two walkways, drops down through the first difficult obstacle, and then it’s spinning, then upside down—suddenly the screen in my goggles goes black. My drone, or rather the one I was following, has crashed. I take the goggles off, feeling a bit shaken but energized, as if I’ve just finished a roller coaster ride. “This course required new things,” Thayer says after the race. “We had to fly slower in some parts in order to have enough battery for the technical parts.” Better known in the sport as A_Nub, Thayer is one of the top drone racers in the world. He won the U.S. Drone Nationals just the week before, and helped represent the United States at the World Drone Racing Championship in Hawaii. The Drone Racing League—a startup backed by $12 million in venture capital from notables like Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and Matt Bellamy, the lead singer of the British alt rock band Muse—are betting that they can translate this FPV thrill ride into a video experience that millions will pay to watch. Drone racing, barely a couple years old, is “blowing up,” in the tech dude idiom of the sport. In barely two years, it’s expanded from a few guys bombing line-of-sight loops in local parks to at least 100,000 FPV hobbyists worldwide (there are no central databases for the new sport, so the numbers are fuzzy). Drone racing grew out of a convergence of several improving technologies: tracking equipment from smartphones, better virtual reality systems, the miniaturization of cameras and batteries. Those advances brought the price of drones (or unmanned aerial vehicles) down to an affordable point. A beginner drone racing setup goes for about $500, and an awesome one for less than $1,000. According to Dronelife.com, estimates of the number of drones sold in 2015 range upward of one million, so the number of hobbyists could be much, much higher. The rapid growth has spawned a gaggle of competing leagues and formats. They’re all trying to turn this hobby into a real sport, with sponsorship deals, codified rules, and broadcast partners. (There appear to be plenty of investors for electronic sports, a euphemism for competitive video gaming, which in just a few years went from nerdy niche to global phenomenon.) In addition to DRL, there are at least three other large U.S.-based drone leagues: The MultiGP-Drone Racing League claims more than 10,000 registered pilots and more than 700 chapters worldwide. The Drone Sports Association sponsored its own U.S. National Drone Racing Championships in 2015 and 2016, and brought pilots from more than 40 countries to its World Drone Racing Championships in Hawaii in 27, all of which were live-streamed by ESPN. The Aerial Sport League plans to open its Tron-inspired Drone Sports World entertainment complex in San Francisco, featuring instruction, races, drone combat, and a store. DJI, a Chinese drone maker, has just opened a similar arena south of Seoul, South Korea. The International Drone Racing Association promotes drone racing worldwide. Most pilots compete in several leagues. Travis McIntyre’s trajectory is pretty typical. McIntyre, 30, started in local races about 18 months ago, won a few, went to the first drone nationals, then became involved with DRL and eventually quit his day job (working at a department store) to race and train full time. “We were wondering how many people would tune in to the first race,” says Nick Horbaczewski, the CEO and founder of DRL, talking about the league’s January event in a Miami stadium. “About 860,000 tuned in for the live race. When we released other content clips and highlights...about 40 million watched.” Competitions are attracting big money: The crown prince of Dubai, along with several Dubai companies and the United Arab Emirates’ transport authority, put up $1 million in prize money for the World Drone Prix in February, paying $250,000 to the English teenager who finished first in the race there. The winner of the U.S. National Drone Racing Championships in July took home $10,000 in prize money, and $100,000 went to the various winners of the World Drone Racing Championship in October. The leagues are experimenting with various ways to fund the sport: MultiGP relies upon sponsorships from the U.S. Air Force and manufacturers of drones and FPV goggles. The USDRA and DRL are pursuing broadcast partnerships to fund their events. ********** “It’s moving so fast,” says Thayer, who won the 2016 Nationals, placed sixth in Dubai, and competed at the Worlds in Hawaii. “I never imagined that I would be doing this, traveling, flying. It’s awesome.” In the midst of this chaos, DRL hopes to set itself apart by focusing on post-production editing that weaves together compelling pilot stories, commentary, and themed races; their main approach will not be to show the races live, but to show packages after the fact. The league announced partnerships with ESPN and international broadcasters; they’ve also signed a content partnership with MGM Television and reality-TV producer Mark Burnett. DRL says it will release nearly 10 hours of programming before the end of 2016, and much more in 2017. The league’s Los Angeles race last March, LA-pocalypse, took place in the gritty, graffiti-covered halls of an abandoned mall in Hawthorne, California. I’m at the July race, dubbed Project Manhattan —they couldn’t use “Manhattan Project” for legal reasons—and it evokes a high-tech factory gone wrong. Fog machines exhale on the course, and neon accentuates many of the check gates. Along the straightaway they’re calling the Ribcage, several ominous robot mannequins stand in what look like Borg alcoves from a Star Trek movie. All this has been set up in the main building of Bell Labs, a legendary research campus in the middle of central New Jersey. The building, about eight stories high, houses a giant core atrium. If laid on its side, the Empire State Building could fit in this interior space. Most pilots I spoke with were sucked into drone racing after viewing a 2014 YouTube video of a race through a French forest, which evokes the speeder bike chase in the forest in Return of the Jedi. Who wouldn’t jump at a chance to race like that, even if only through FPV goggles? Between heats at the DRL event, pilots huddle around laptops with friends, sponsors, and coaches on man-cave leather couches, deconstructing videos of the latest heat, or the latest drone sensation on YouTube. Guys—virtually no women are here—high-five, sip bottled water, and laugh. Even with big money at stake, the competitors seem at ease giving one another tips and advice. Most drone racing pilots seem unusually cooperative and willing to help out the newbies. “The drone racing community is extremely close,” explains Tony Knittel, whose race name is Kanoodle and who has been brought in as a kind of Bob Costas to announce for the Project Manhattan DRL event. “This sport evolved from the hobby world, which is a wonderfully helping community,” he says. Zachry Thayer (A_Nub), Jordan Temkin (Jet), and Travis McIntyre (m0ke) live together in a rented farmhouse outside Fort Collins, Colorado. They’ve turned the enormous basement into a tech workshop. They practice together in their one-acre yard, or zip their drones around the cliffs and peaks of the Rocky Mountains. Sometimes Thayer and Temkin compete together as Team Big Whoop, as they did at the Dubai World Drone Prix and Drone Worlds in Hawaii. All three competed at the DRL Project Manhattan race. “None of us got into this for anything other than fun,” says Thayer. “We’re working together to grow it.” YouTube and Facebook host growing communities of drone racers; message a top drone pilot on social media, he will most likely answer. “The learning curve is pretty steep,” says Trace VanGorden (Von Quad), the host of the Quad Talk FPV Drone podcast. “It encompasses so many different mediums of science, aerospace, programming, engineering—you can go pretty deep in the water when you start.” “I love the tech, being able to engineer my own parts,” says Thayer, who designs and sells racing drones. Engineering savvy can give can give competitors an edge in races in which pilots design and fly their own drones. Most race quadcopters, but some race drones with three or (more rarely) six rotors. In some races, the drones would be dangerous if you got in their way; an Australian group just claimed that their 66-pound, five-foot-wide racing drone bested 200 mph. Others are small enough to fit in your palm and safe enough to buzz around a bar. DRL differs from most other leagues in that all pilots at its events use proprietary DRL quad drones. Just before one of the heats, a DRL exec takes me back into the pit behind the race officials and the pilot stands. Dozens upon dozens of DRL drone bodies have been laid out in ranks on several tables: each an LED-bedazzled black carbon-plastic brick housing a battery and four arms extending from the corners for the rotors. A few engineers are repairing drones that crashed in the last race. Others are sifting through piles of rotors; still more people are getting drones ready for the next race. At almost two pounds, DRL drones weigh more than most racing drones, but they’re also more powerful. With all pilots racing with the same type of drone, the competition focuses on piloting skills alone. The DRL drones are built to be sturdy, so they don’t break as easily as commercially available models. And because the pilots aren’t racing drones they own, they’re more likely to take risks. There’s no financial downside to just going for it. MultiGP Drone Racing allows pilots to race their own modified drones through a course. (Travis Fausey/Multigp) “The fact that they’re on the heavier and larger side brings out the best racing I’ve ever seen,” explains Thayer. “By limiting the performance of machine, it forces a pilot to be a better pilot, to be the best they can be.” The main obstacle in this multi-level Bell Labs race is an eight-foot-wide open cube that DRL has dubbed the Atom. In order to follow the course, each pilot has to do a split-S maneuver, swooping into the cube, flipping over, then swooping out in the opposite direction, thereby “splitting the Atom.” I stand with DRL’s Nick Horbaczewski in the middle of the Bell Labs atrium, at a line of police barriers and nets that bisects the course, keeping people from getting in the drones’ way. Safety is a top concern; rotors can slice quickly and some pilots even carry QuikClot, a coagulation agent, in their backpacks. Behind us sit the pilots, the pit, and race officials. In front of us, the Atom has been suspended a couple stories up. Horbaczewski, who previously worked at the extreme sports company Tough Mudder, looks like he’d be just as comfortable backpacking in Yosemite as running a race in this high-tech arena. We lean on the barriers and watch a couple heats. The pilots have to let their drones fall through the top of the Atom cube, flip, then punch the speed to get out of the bottom, while also managing to avoid slamming into the atrium floor. Even to the uninitiated, it looks difficult. Damn near impossible, really. And that’s the point.

DRL Unlike MultiGP and other leagues, DRL allows only one standardized drone. Races are won by savvy piloting, not technical innovations. (Drone Racing League) “One of the things that people love is crashing,” Horbaczewski explains. “We knew that the Atom would cause a lot of crashing. In drone racing, there’s none of the moral hazard of Formula One racing. No one dies.” Drone racing controls aren’t as easy as a phone app that levels and flies a camera drone; it’s much more hands-on and difficult. Pilots hold a thick control console and manipulate two small joysticks. The left stick controls throttle and yaw; the right controls pitch and roll. Drones have no rudders or ailerons; altering the speeds of the rotors changes the drone’s direction, attitude, and speed. When flying down a straightaway, they fly at a backslash angle, as the back rotors push the drone along. “It’s like an Indy car in the air,” explains Knittel, the announcer. “It’s not going to just hover around and get groceries.” Yet as the drones whip around the course like angry bees, the six pilots in each heat sit straight-backed and still. They could be Zen monks, but instead of meditation cushions they have funny goggles. Their only perceptible movement is in their thumbs, twitching ever so slightly. As at the top levels of so many sports, it really comes down to psychology, the ability to perform under pressure. “Hand shakes” is a problem most pilots say they have experienced. Walking past the pilot rest area, I hear a coach advising, “Stay calm; don’t worry about trembling. Remember it’s just a game.” “M0ke” McIntyre says that drone racing for him is “an out-of-body experience.” “When I’m flying and have the goggles on, I’m so focused,” he explains. “I won’t hear the music in my headphones. I escape reality. It’s like being a little bird flying around in the sky.”

Travis “m0ke” McIntyre (center) and Ken “Flying Bear” Loo (left) were finalists at DRL’s Miami race, but eventually Steve “Zoomas” Zoumas (not pictured) came out on top. (Drone Racing League) The tough bit is taking that pilot experience and making it accessible to a mass audience. DRL has released a multi-player drone racing video game, and many in the field think that someday it might be possible for viewers at home to “follow” a pilot in FPV goggles, just as I did at Bell Labs. Obviously, that tech will take a while to develop. For instance, the goggle feed now is grainy, because anything crisper would create a time lag greater than 20 milliseconds, the max allowable for racers to react in real time. For now, watching a drone race in real time is a bit like going to the horse races. There’s a lot of waiting, and each heat seems to be over in moments. And for a drone race to get off the ground, a lot of tech has to work right. Radio frequencies can interfere, or “stomp” each other. In some leagues, Knittel and other pilots say, races frequently get off schedule. Races can be an adrenaline rush, but in between there’s a lot of down time. There’s also the problem of high expectations. We’ve all gotten used to the thrilling CGI video of Harry Potter Quidditch and Star Wars pod racing. But think of actually trying to film something similar in the real world: How do the cameras get up close to things that are moving so quickly and so unpredictably? How do they do this over a large course? At this point, DRL is relying on the drone cameras, 35 stationary cameras around the course, 360-degree video, and skillful film editing by a team of videographers. Sitting in the stands, I watch as one drone ditches in the fountain soon after lifting off. Another two looping from floor to floor crash. Two more collide trying to get through the Atom. Not one of the six drones from that heat finishes. No matter. The next heat will see six more whiz into the air."

On October 27th, 2017, Pocket-lint said, "DJI has revamped most of its drone series' this year. None more so than the Phantom series. We saw replacements for the Phantom 4 and a new Phantom 4 Pro. While the original Phantom 4 Pro looked very much like the original Phantom 4, the Obsidian Edition brings a new Stealth Bomber colour scheme. But can the technology inside this newer drone match its new lick of paint? How does the Obsidian differ from the Phantom 4 Pro?

350mm diagonal; weighs 1.38kgs Magnesium alloy camera housing 5-direction obstacle avoidance

The Phantom 4 Pro Obsidian looks the same as the regular Phantom 4 Pro, except for one major aspect: it's black. This might seem like an unimportant cosmetic change, but it does mean you can see it more easily against the sky when the drone is in flight. It seems kind of obvious, but the sky is generally bright and clouds are typically white on a good day. So remaining on the ground, facing up at the heavens, while flying a white drone can lead (often) to losing sight of it quite easily. This is especially true if you accidentally fly it directly between you and the sun, or just quite far away from launch. With the Obsidian edition of the Phantom 4 Pro, this was rarely an issue. The dark grey/black colour scheme makes for a more easily visible silhouette. Unlike the Mavic Pro, the Phantom 4 Pro Obsidian is a large, fairly rigid drone. There aren't any folding parts, meaning you need to carry it around in a rather large protective case that's hewn from a chunk of dense Styrofoam. In order to keep things from getting insanely difficult to transport, DJI had the wisdom to make the rotor blades removable, like previous generations of this drone. When you take the Phantom 4 Pro out of its case to go fly, you attach these blades, then detach them when you're done. It's a minor inconvenience, but one thing you don't ever have to do with the Mavic Pro - unless a blade breaks and needs replacing. Despite its size, the sumptuous curves on top and beneath the Pro 4 give it an attractive look, while the slender legs provide a sturdy base for the drone to stand on, and give the under-hanging magnesium alloy-clad camera the space it needs. One thing you will notice around the drone's body are a number of small blacked-out areas and circular sensors. There are two cameras built into the front legs, two on the rear, and a couple on the underside. In combination, these six cameras give the drone its 5-direction obstacle avoidance.

The back of the Phantom 4 Pro Obsidian is where you'll find the removable battery. It has the usual set of LED lights, and the LED ring around the power button on the outside, as well as grippy rectangular buttons on top and beneath. These buttons, when pressed in unison, release the battery, so that you can slide it out for recharging. Does the DJI Phantom 4 Pro come with a controller?

Remote control with screen in "Pro+" package Remote has 5.5-inch Full HD display 7km remote control range Standard pack utilises your phone via app control

Depending on which 4 Pro package you end up buying, the flying experience will be slightly different. The Pro+ package that we tested costs £230 more than the standard package, but it comes with a screen-equipped remote. Otherwise you'll have to use your smartphone as a remote, via an app. The entry Phantom 4 Pro comes with the basic remote that needs a phone to view the live video feed. In our experience, paying the extra is a no-brainer. Having the screen already there means no fiddling around trying to get your phone plugged in and secured into a grip. It also means you only have to worry about two batteries draining - not three. Despite its professional qualities, actually flying this Phantom 4 drone is relatively easy. After all, the high-tech sensors mean that the drone does all the nitty gritty hard things for you. In other words, you let go of the controls and it'll hover in place without being bothered by the wind (presuming you don't try and fly it in gusts over 22mph).

We tested the Pro 4 in some very strong mountain winds and, while it stayed airborne, it struggled to hover in place - instead it constantly drifted. So, yeah, don't do that. Controlling the Phantom 4 Pro uses a combination of the traditional joysticks, buttons and scroll wheels on the remote and the touchscreen-based user interface. For basic controls - taking off, moving the drone and adjust the camera angle - you can use just the physical remote, using the screen purely as a live video feed. For more advanced features - like the various flight modes - the touchscreen is indispensable. From the touchscreen you can choose which of the ActiveTrack modes you want to use. This tracking mode feature is where you can draw a rectangle target around a person or object to have the camera or drone to follow them. You can also use a Draw mode - where you literally draw a route with your finger on the screen, tell the drone how fast to fly, which it then follows. There are many other flight modes, too, such as the ability to set a point of interest and have the drone circle around it, or TapFly which allows you to tap on any point visible on the screen and for the Phantom to then fly to that point. Of course, there's the now famous Return To Home feature, which does exactly what it says on the tin. Once activated, the drone flies back to its recorded home point, hovers to find its precise take-off position and then lands itself. All you've had to do to activate this is either press a button, or slide your finger on the screen. One thing that impressed us most about the drone's various flight modes was how well they all worked in testing. Not one of the various methods of flying or tracking failed seriously.

ActiveTrack precisely followed what we told it to follow, and the only real issues arose when the person it was following was partly obstructed from view. Once they came back into view, the ActiveTrack system was able to pick them up again fairly reliably. Similarly, the Draw mode worked flawlessly, smoothly following a virtual line we'd drawn on the screen. Similarly, every time we tried the Return to Home feature, the drone landed precisely where it had taken off from, within centimetres, and this in an area of grass which was seemingly indistinguishable from the rest of the area it was in.

How long does the DJI Phantom 4 Pro last per battery?

5,870mAh battery Up to 30mins flight time

Perhaps the most important improvement in the Phantom 4 Pro, however, is its battery life. In DJI's sterile, windless testing environment, the Phantom 4 Pro can last 30 minutes of flying. In real life, you'll get less time - but still much more than we were ever able to achieve with the Mavic Pro or tiny-scale Spark.

Even with slight wind, while testing various flight modes and with almost constant video recording, the 4 Pro was capable of lasting 20-25 minutes per battery in our use. Get a spare battery and you'll have the peace of mind that comes with knowing you can fly for almost an hour, without having to worry about getting that anxiety-inducing "low battery" warning.

How good is the DJI Phantom 4 Pro's camera?

1-inch CMOS sensor 20-megapixels 4K video recording at 30fps

As drone cameras go, the Phantom 4 Pro's is among the most impressive in the spec department. It has a 1-inch CMOS sensor which boasts 20-megapixels and the ability to record at various resolutions, up to 4K at 30 frames per second. It's the end result that are most important, though, and in our testing we find its results to be among the best looking footage and stills we've seen from a drone camera. That's perhaps not a surprise given just how much larger a 1-inch sensor is than many smaller-scale competitors.

Still photos are vibrant and full of colour, which is exactly what you want when shooting cinematic landscape footage. Sometimes when shooting in contrasting light conditions, the 4 Pro struggled not to overexpose the highlights, while trying to keep the rest of the shot balanced. Even more impressive is video, because it's so impressively smooth. Details are sharp too. This is thanks mostly to the gimbal system the camera is mounted on. Flying in some wind, the 4 Pro's camera footage looks completely steady and shake-free; similarly, camera movements (even when you don't feel like you're controlling it smoothly) are silky smooth.

Verdict If you want the best consumer drone around, look no further. The Phantom 4 Pro might not be as nimble and portable as a DJI Mavic, but it makes up for that by being powerful, reliable and longer-lasting, too. Add stable, attractive and smooth results from the 4 Pro's camera and you have a drone which feels impossible to beat at the high-end of the consumer drone market. It's very impressive indeed.

Alternatives to consider The Mavic Pro is less expensive, much smaller, and has a lot of the same flying capabilities as the Phantom 4 Pro. It may not last as long, or be quite as honey-smooth as the Phantom 4 Pro, but it will fit in your backpack and leave you with more money in the bank... quite a lot more money, in fact. GoPro's first drone is much more affordable than the DJI, especially if you're an existing GoPro camera user. You might not get all the high-tech features of the Phantom 4 Pro, but you do get a drone that's even more effortless to fly thanks to the super user-friendly remote control and user interface.

font-size: 20px; Ultimate beginners-guide-to-fly-a-drone Editor’s note: drone ground school Looking for some serious help in becoming a better quadcopter pilot? We recommend Drone Pilot Ground School Check It Out! An at-home drone ground school training course for sUAS pilots looking to pass the FAA Aeronautical Knowledge test and to become certified drone pilots. **Update – Get $50.00 OFF Drone Pilot Ground School when you sign up by clicking the link above!** Notes On Drone Pilot Ground School I personally know Alan over at UAVcoach.com and he is definitely a stand up guy and knows his stuff. He has put together an excellent course here so take advantage of it! As restrictions have been changing every few months, and federal rules and regulations are becoming a highly unavoidable issue, an above average pilot school is recommended for those newly getting into the camera drone hobby. Learning how to navigate the drone itself is one thing, but the last thing you want is to not know the exact fly zones or other protocol in your area and incur a fine or other trouble. Drone Pilot Ground School is an excellent at-home training course for UAS pilots that want to pass the FAA Aeronautics Test, and become certified in your area. This is a very solid and easy-to-understand approach to not just operating the drone, but understanding the weather elements that affect you while piloting, and the National Airspace System. Drone laws and regulations, operating rules, and the remote pilot certificate and waivers are the first components of this coursework: these are some of the issues that will be updated frequently and constantly changing. An in-depth look at the ways in which weather affects all small aircraft and micrometeorology is also here in the content, so you as the pilot can fully understand issues regarding wind, and how the changing conditions can alter your flight. Another one of the most important subjects taught here is knowing FAA airspace classes: this is some of the real meat and potatoes and solid information that will keep you alert and up to national and local standards regarding where you operate. Airport operations, radio communication procedures, as well as loading and performance are all looked at in-depth as you glean over Drone Pilot School material, which also goes over emergency operations preparedness. After this course, you will be able to deal with payload and gimbals, have vast knowledge of official regulations, and even touch on expert-level topics such as Physiology. Following in this article is some information about learning to fly for those of you out there that are not needing professional certifications. It can be fun to just take the drone out to a park or open space, and enjoy the hobby of flying, and some don’t feel a need to bypass the beginner drone level. We’ll take a look at the best quadcopters to purchase for beginners, the basics of maneuvering around in the air, and the different flight modes you’ll encounter on your brand new drone. Shop Related Products The Pilot's Manual: Ground School (PDF eBook Edition): All the aeronautical… $42.25$59.95 (52) Ultimate Beginner Keyboard: Complete, Book & DVD (Sleeve) (The Ultimate B… $26.47$29.99 (6) Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge $7.50$24.95 (259) EACHINE E010 Mini UFO Quadcopter Drone 2.4G 4CH 6 Axis Headless Mo… $20.99 (1299) Remote Pilot Test Prep - UAS: Study & Prepare: Pass your test and know wh… $14.93$19.95 (131) Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (2017 Edition): with Advisory Committee Note… $17.99 (4) Weather Elements (Clouds, Precipitation, Temperature and More): 2nd Grade Sci… $9.42 (1) Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge: FAA-H-8083-25B (FAA Ha… $16.96$24.95 (259) Ads by Amazon Learn To Fly Drones by Oscar Liang There are probably more newbies out there anxiously looking for guidance, tips and actionable hints to help them enjoy this amazing hobby safely than ever before in history. That is due to the fact that last Christmas was the first year when one of top stocking stuffing choices was drones. It makes sense after all, you have bought the new iPhone last year, the new iPad the year before, you ran out of ideas and your beloved spouse is a technophile. You can not go back to a scarf or socks and the media is blasting drones, drones, drones. Of course you will buy a multicopter. And that is a good choice as long as the on receiving it handles it in a safe and liable manner. Want to learn about the best drones to buy? Check out our drone buying guide. So I feel that instead of mocking newbies (or “noobs” as some like to call them), we should help them as much as we can. After all we must also remember the first day we handled a transmitter and flew for the first time. We have not been confident at all and had to make mistakes in order to learn to fly drones. Anyone denying that is lying. Probably to himself also. Nobody is born with an inherent knowledge of flying copters. I was extremely surprised by the mockery in the comments to the video of a poor newbie that we posted the other day who almost sent his Phantom 2 into the pond on the first day he flew it (the battery depleted). These more experienced RC “pros” laughed at him, called him names and clearly had no sympathy for him. I totally feel that this is wrong. If you have done RC flying for 10-15 years, chances are that the next generation will be much better at using this technology than you. So instead of being boastful, I feel that we should help newbies to gain enough confidence and experience to fly safe enough to enjoy the hobby. After all it is in our interest also because that way they pause less risk to the hobby getting banned entirely and if they are happy drone pilots, they will inspire others to fly as well. So here is a great initial guide from Oscar geared at newbies wanting to learn to fly drones, multicopters: New to Quadcopters, Where to Begin? This guide is intended to help quadcopter beginners get started and learn to fly quadcopters and other multirotors. Multicopter flying is fun and it’s a relatively new and emerging hobby. There isn’t much information for people when they start out, so very often they just pick up the radio controller and start to fly around without knowing anything. It’s important to know that quadcopters are pretty powerful machines with fast rotating propellers, you can easily break or damage what it crashes into. To minimize the risk it’s important that you follow the rules, and avoid flying over or near people and property, or any restricted area without permission. Best First Quadcopter for Beginners It’s always a good idea to get a cheap, robust “ready to fly” mini quad to start with. It’s also a good choice for presents and gifts for someone who wants to get into this hobby. They are usually under $50, so it’s easier to deal with if you crash, than having a $500 quad. Also they are a lot smaller and lighter, it causes a lot less damage to people or objects. Although there are expensive and advanced flight controllers and copters that offer amazing GPS stability and assisted flying modes, you still need to be a good pilot to handle all sorts of situations. I don’t remember how many times I have seen someone posting a request online looking for a missing “fly-away” Phantom, or a picture of their wrecked costly quadcopter after maiden flight. I bet a high percentage of these incidents were due to inexperienced pilots. It might save you money to go straight to the quadcopter or setup you want, but learning on smaller, more crash-resistant nano quads benefit you in the long run. Looking to protect your drone from a flyaway? Check out our recent post on uav tracking! Radio Transmitter Control Explained If you have ever played games with game console, the Radio Transmitter is very similar. Here is a diagram of the controller, showing what each control does to the quadcopter. learn-to-fly-drones You have two main sticks for the throttle and direction control, and you will have some optional switches as well (aka AUX switches), which are often used for switching between flying modes, turning on/off LEDs, etc. Throttle Makes the quad ascend (climb) or descend (come down). Yaw Rotates the quadcopter clockwise or counter-clockwise. Roll Tilts the quadcopter left or right. Pitch Tilts the quadcopter forward or backward. These controls are also referred to aileron (roll), elevator (pitch) and rudder (yaw). Quadcopter Flight Modes There are many different flight modes (stabilization modes) for a quadcopters, depending on the kind of quadcopter or flight controller. The most common flight modes being rate mode (aka manual mode or acro mode in KK2 boards), Self-level mode (aka horizon mode in multiwii, Naze32), Attitude mode, GPS hold (aka Loiter mode) and so on. Each flight mode is designed for different flying purposes, and might use different sensors and electronics modules. For example for the self-level mode, it uses the Gyro sensor and accelerometer, and the copter will always try to balance itself when you are hovering. But manual mode only uses Gyro, and the copter doesn’t level itself. Once you tilt it, it just keeps going that direction until you manually correct the angle, thus the name “manual mode”. Self-level mode is good but it’s not perfect, you will still find the quadcopter drifting around. Also it tends to wobble and vibrate a bit because of the the fact that it’s constantly trying to balance itself. Therefore many FPV’ers including myself prefer to fly in rate mode, and the result is a lot more smoother, and it becomes fairly easy to control too once you get used to it. However I still recommend new people to try self-level mode first, to build up experience and confidence. Manual mode can be very hard to control for someone just beginning to fly. Most cheap nano quads come with self-level mode, some even have the optional rate mode available. Good Beginner Drones When picking out a starting drone, you’ll want to look mostly at durability, ease-of-use, and price. Durability is important because first-time users always have a few crashes, and you don’t want to trash your new toy when you’re first getting started. Ease-of-use is obvious – a high-end drone like the Phantom 4 might have a ton of great features, but to a beginner those are just complications you don’t really want to deal with. And in case something does go wrong, you want to start with a fairly cheap drone that won’t set you back thousands of dollars.table drones under 150 altair aa108 Our personal recommendation is the Altair Aerial AA108, which we did a full review of here. Short version: the AA108 is a phenomenal choice for beginners because it’s extremely tough, has a lot of beginner-focused features that make it really easy to fly, and only costs $130. It’s an all-around good choice that gets more difficult as you get more capable thanks to multiple speed modes and flight patterns. Fair warning, though – it doesn’t do well in wind, so you might want to avoid it if you live in someplace with a lot of inclement weather. You can read reviews and shop for the AA108 here. How to Fly Quadcopters and Rules Here we begin talking about how to actually fly the quadcopter. First, here are some safety rules. Pick a nice day with no wind. Go to a large open field with no obstacles such as buildings or power lines around. Keep distractions at a minimum, and switch off your phone. Make sure you don’t fly near people or properties. Now it’s time to practice your skills. Taking off and climb a couple of meters, hovering, flying from point A to point B, and landing. Take it slowly. Wind Speed This is probably the first thing you need to find out before your flights, if you are flying outdoors. I personally would not fly if the wind is stronger than 15mph. It’s flyable, but the the quad will be a bit wobbly and the video footage will be a bit shaky. Before I understand how important this is, I flew my 450 size tricopter in gusty wind (it must have been 25mph – 30mph) and it didn’t end too well. It was totally uncontrollable, eventually it was pushed away by the wind and crashed pretty badly. So you need to know the limits of wind speed your quadcopter can handle and don’t risk it flying in powerful wind. Practice Hovering Hovering is actually harder than it seems, especially when you are flying FPV through a monitor or FPV goggle. Mastering hovering does not only allow you to have better control over your aircraft, but also allows you to shoot better aerial videos and pictures. Cut Throttle When you are flying forward fast, and you are about to crash intro a tree, what would you do? If you can escape by turning left or right, a wise option would be turning off your throttle. By stopping throttle, you also stop the fast rotating propellers as well. This reduces the chance of breaking your props, motors and further damages to your quadcopter. Some nano quads come with prop guards which are also good features to consider. jj600-quadcopter-feature Unfortunately crashes are inevitable, even for the experts and pros. The best you can do is to learn how to minimize the breakage. I hope this short article gave you some basic ideas about quadcopters, and how to fly one. There is indeed too much information to cover in just one article so do check out my other pages as well. Have fun and fly safely. We recommend Drone Pilot Ground School Check It Out! An at-home drone ground school training course for sUAS pilots looking to pass the FAA Aeronautical Knowledge test and to become certified drone pilots. Check out our new best drones for Christmas 2016 article. Summary Quadcopter Beginner's Guide | Learn to Fly DronesArticle NameQuadcopter Beginner's Guide | Learn to Fly Drones DescriptionThis guide is intended to help quadcopter beginners get started and learn to fly drones and other multirotors. AuthorOscar Liang